The Meek prevails

There is a movie coming out about Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, which reminded me of two humiliations I suffered at the hands of a guy named "Meek." I promise this will make sense in a few paragraphs.

My hometown, Hudson, NY, celebrated its bicentennial in 1986. There were parades, special issues of the local paper, The Register-Star, and a five-mile run to celebrate the city's birthday. I worked at the newspaper and my terrific editor, Jim Calvin, proposed that I challenge one of our colleagues, Mike Meek, to run in the race. "C'mon, help promote the race," he said, knowing full well that I was as physically fit as a corpse. When Jim was not encouraging you to spell words correctly by throwing a dictionary at you, he was very charming and persuasive. I said, "I'm in."

Mike was the paper's city of Hudson and politics reporter and a good one. He became like a brother to me and often I would find him at my parents' house helping himself to a serving of my mother's spaghetti and meatballs. Or he'd be in the family room having a beer and watching the New York Giants with my father. My parents' couch cushions had a Meek-shaped imprint.

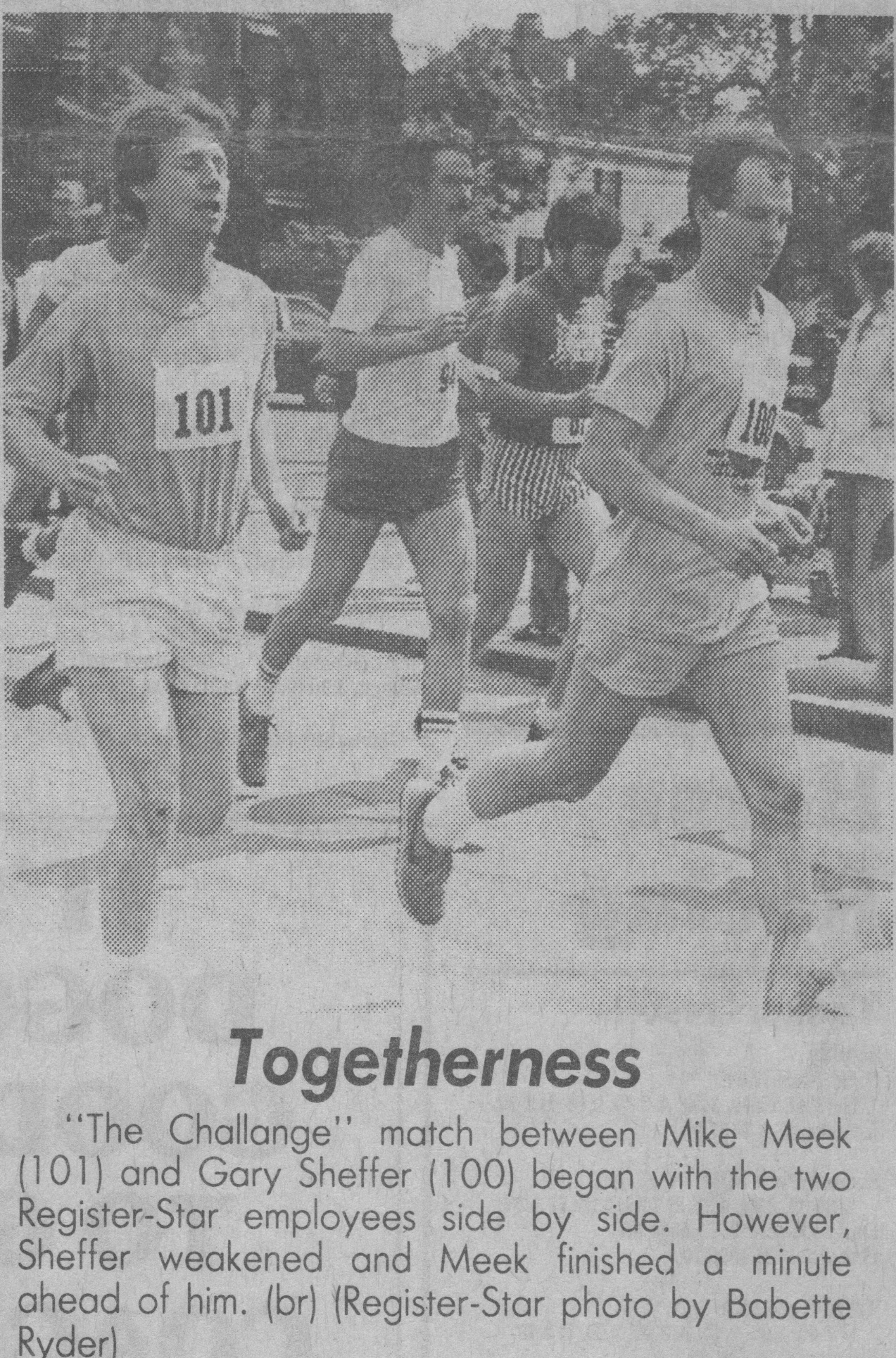

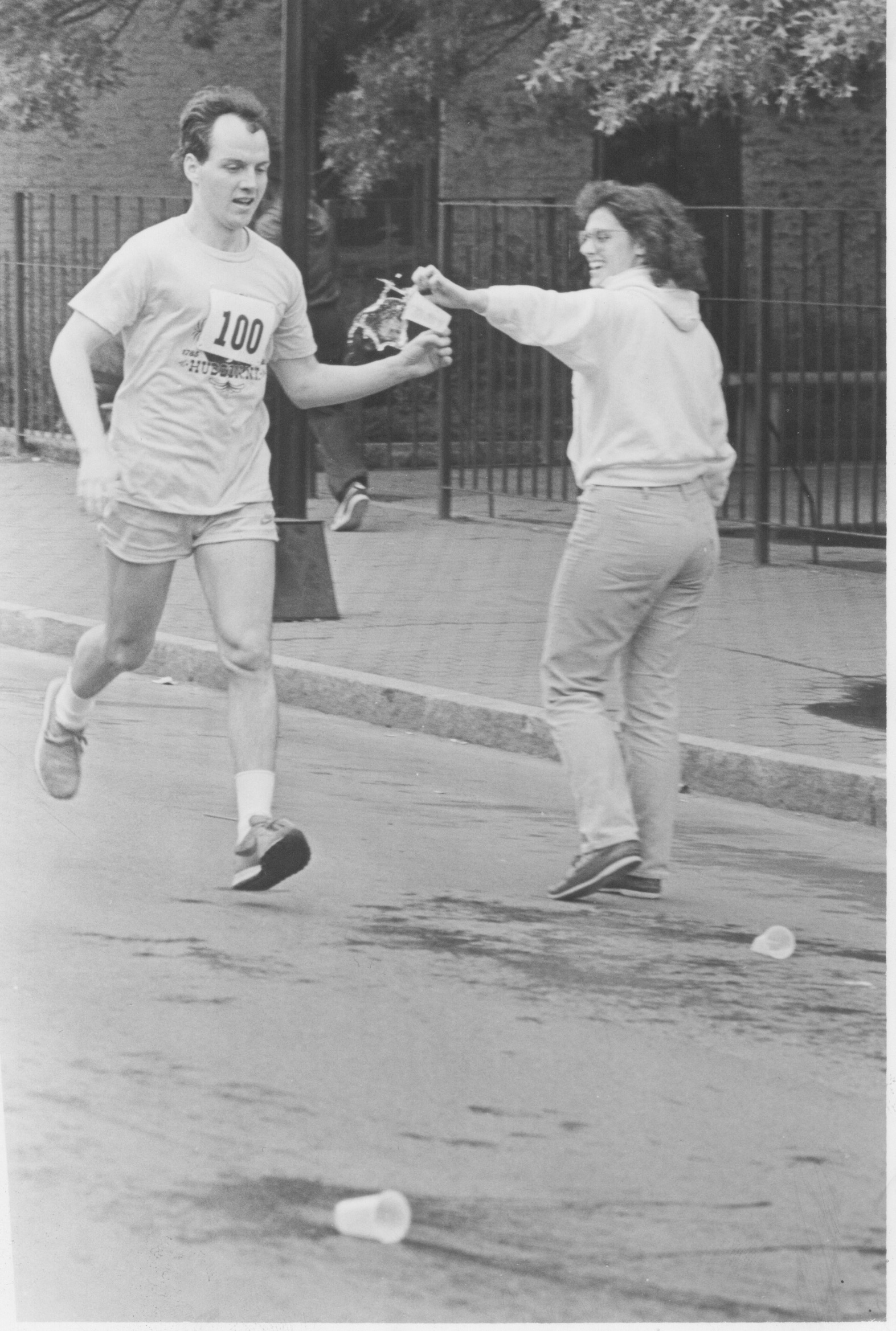

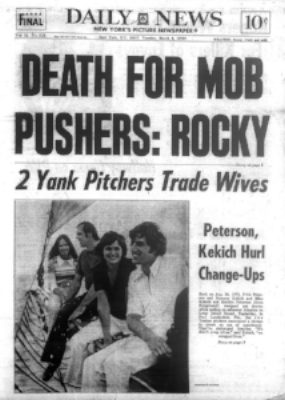

I lost the race but, man, look at my hair.

Mike accepted my race challenge, which we made public by writing about it in the Register-Star. It was billed as the hometown boy -- me -- versus the carpetbagger from downstate -- Mike. We traded taunts and promises of victory -- sort of like a written version of a boxing weigh-in. Mine were better -- I accused Mike of being the only man I knew who had cellulite.

I may have won the verbal battle, but Mike won the war. To put it mildly, I undertrained and underestimated Mike. He whipped me -- I never saw him after the first mile. As part of our agreement, I wrote an apology in the newspaper for letting down my hometown. It began:

"Sorry Hudson High, my regrets Coach Leamy, I apologize Charter City.

"It was a semi-glorious weekend for Hudson. On Saturday the winds whipped away the clouds for the Bicentennial parade, on Saturday night fireworks blasted across the city's skies, and on Sunday Mike Meek blew me away in the Bicentennial Run."

But I didn't hold it against Mike. He was in my wedding and I was his best man. He married a beautiful professional dancer from Argentina, Valeria Solomonoff. I did my best man's toast in Spanish quoting Neruda's poetry. Here's what I chose from Neruda's 100 Love Sonnets:

"I love you without knowing how, or when, or from where. I love you simply, without problems or pride: I love you in this way because I do not know any other way of loving but this, in which there is no I or you, so intimate that your hand upon my chest is my hand, so intimate that when I fall asleep your eyes close

You need a tissue, right? I thought this would bring down the house with "awwwws." Unfortunately, my delivery was in mumbling, halting Spanish and the whole thing, to me, was more awful than awwww.

That's my future wife, Barbara, and I misconnecting at a water stop.

Next up was a bridesmaid, Mariucchi, a professional singer. As I sat down, the room went dark and then a single spotlight dramatically illuminated her, microphone in hand. She performed a beautiful ballad for the wedding couple. It brought down the house. I was so glad I went before her.

Valeria and Mike then read a Neruda poem to one another (thankfully not the one I had read!), and did a traditional tango, which Mike pulled off magnificently after weeks of practice. Then Mike and Valeria's friends, many of whom were professional dancers, joined them on the dance floor. The room was filled with stylish, talented young people who obviously loved Valeria and Mike.

This was totally selfish on my part but, at the time, I felt like I -- meaning my toast -- had finished second again. I was grateful that Mike didn't warn me about the "floor show" that followed my toast because I would have sweated through my tuxedo. Nonetheless, the wedding was a blast and one of the most joyous I can remember attending.

Today, Mike and Valeria have two beautiful children and live in Manhattan. Mike wisely moved from journalism to finance after earning his MBA from New York University. He informs me he retired from competitive road racing after beating me, figuring he had reached the peak of his potential. I have run dozens of races since then, perhaps trying to erase the memory of my loss to Mike.

Recalling these moments is fun but leaves me a little wistful. Let's see, what can pick up my spirits? How about a little more Neruda?

"So I wait for you like a lonely house

till you see me again and live in me.

Till then, my windows ache."

Awwww.