Fritz, Mike and me

The great novelist Richard Russo (Empire Falls, Nobody’s Fool) is a remarkably keen observer of small towns and the flawed, funny and unforgettable people that inhabit them. I love Russo’s work, partly because his towns are in upstate New York, where I grew up listening to the stories from and about quirky, eccentric and endearing characters.

I have been reading a lot of Russo lately and it reminded me of a story from my hometown of Hudson, NY, a historic former whaling port 40 miles south of Albany on the Hudson River (parts of the movie Nobody's Fool were filmed in Hudson). My story isn’t quite up to Russo’s high comedy but it does tie together my love of the Yankees, baseball and how a young boy reacts when blindsided by his heroes.

Nearly every hour of my childhood (even when I was in school) was filled with sports – reading, thinking, playing and watching them. Baseball was my favorite and I was a Yankees fanatic. Sadly, my Yankees weren’t the champion Yankees of Munson, Jackson and Nettles that would emerge in my late teens.

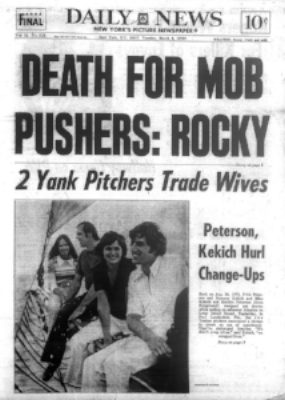

The Daily News treated the trade with subtlety and sensitivity. From left: Marilyn Peterson, Mike Kekich, Susanne Kekich, and Fritz Peterson.

My Yankees were the awful but lovable Horace Clarke, Jerry Kenney and Jake Gibbs Yankees that sleep-walked through games and usually were out of the pennant race by July. In the late 60s and early 70s, the great shrine of baseball, Yankee Stadium, had become a doleful, dirty and deserted place.

Despite that, I still loved watching them on TV but you could only see them if they were on NBC's Saturday game of the week, which wasn't often because they were, well, bad. Then a miracle happened -- one of the local stations picked up the Friday night WPIX broadcasts of Yankee games. My cousin Mike and I prepared for every game by riding our bikes to Kenneally’s corner store to get soda, chips and candy. Unfortunately, the combination of M&Ms, bubble gum, barbecue-flavor chips and Coke combined with another woeful Yankee performance usually made us nauseous.

The Yankees’ incompetence did not deter our fanaticism. We collected Yankee trading cards, wore their hats and remained immovable in our optimism. One day my father brought me 4-by-6 inch color photos of a few Yankee players (I have no idea where he got them). Among them were pitchers Mike Kekich and Fritz Peterson. Remember those names.

The Yankees were the perfect team for me as a player because I was as bad as they were. Every year at the Hudson Little League banquet, a Yankee – such as outfielder Bill Robinson or shortstop Gene Michael -- would speak and present the best players with trophies, none of which bore my name.

When I was 11 the speaker was Peterson, a good left-handed pitcher and an All-Star in 1970. I was shut out of the awards but I didn’t care because I was seated 20 feet from a real Yankee. I carefully studied Peterson like the fanboy I was -- how he ate, what he drank, how he walked. If it worked for him, maybe it could for me.

That's Mike Kekich in the upper right of the photo and me directly to his left in my brother's sport coat and tie at the 1972 Hudson Little League banquet.

By the time I was 12, my team – the Bucks – and I had improved enough to get a few trophies. Kekich, a mediocre pitcher and Peterson’s best friend, presented me with my baseball trophies. I also had won the local Punt, Pass & Kick football competition and was called forward to get that trophy.

Kekich handed me the statuette and then punched me in the arm – hard -- and said “I thought you were a baseball player.” I was too lightheaded to respond – a Yankee had spoken to me and actually punched me in the arm like we were buddies. I went back to my table, my arm still smarting a bit and said to my brother, “Holy shit, did you see that? He punched me!”

Needless to say, Peterson and Kekich became my favorite players and I put their photos on the top of the set my father had given me.

Sadly, the bromance soon ended when the strangest trade in baseball history happened. In March 1973 Peterson and Kekich announced at Yankee Stadium that they were trading wives. Yes, wives. Actually, they were trading families, kids, dogs and all. I was completely confused when I read the Daily News story. How in the name of Mickey Mantle do you trade wives?

But they did. Yankees General Manager Lee MacPhail is said to have quipped to the press that day, “We may have to call off Family Day.”

Compared to today's athlete misbehavior, this may seem tame – maybe even a funny and touching love story for some "rom-com" writer. But in 1973 it was a big scandal for the staid Yankees. By June, Kekich was trundled off to the lowly Cleveland Indians. I sent my Peterson and Kekich photos to the bottom of my trash can.

Peterson is still married to Susanne Kekich; Kekich and Marilyn Peterson never married and later split. Kekich later said he felt "left out in the cold" by the whole thing. There has been talk of a movie involving Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. If it gets made, two things should happen: first, Russo should write the screenplay; and, second, I should play the shocked “say it ain’t so” young baseball fan. Makeup!